From Niches To Riches

How the internet has shattered the world into niche markets that you can profit from.

The Internet's Opportunity Machine

The past couple of Stew’s Letters ("How To Get Rich" and "Genius Can't Be Taught") have made the case that if you can learn how to do something that society is unable to teach, and it just so happens that your “something” is valuable, you may be rewarded handsomely since you’ll have little or no competition.

This is more of a mental model than it some clear game plan, but it stands in contrast to the more traditional approach to career planning where we look at what the world is hiring for today, invest in formal training, and begin to climb the metaphorical ladder in our chosen field, mostly keeping our skillset within the boundaries defined for us by the system we’ve chosen to be a part of.

The traditional approach makes practical sense and I don’t doubt it still works in plenty of contexts today; it’s also the only realistic road for a huge number of people.

But the rise of the internet over the past two decades has opened up enormous opportunities for those of us who want to carve out our own niche in the universe rather than occupying a toenail of somebody else’s.

What’s so special about the moment in history we’ve found ourselves?

The internet is an opportunity machine that does one thing particularly well: it creates a playing field where seemingly obscure, niche things have a far higher likelihood of becoming a successful business than ever before.

First, a quick refresher on what the world looked like in the not-too-distant past.

What the world used to look like

For the past hundred or so years, the world has looked something like this:

A handful of companies controlled the means of distribution and defined a relatively narrow set of goods and services that represented our choices as consumers.

In the U.S., all of us watched some subset of the same TV channels, every grocery store in town stocked identical brands of soap and cereal, and it didn’t make a difference whether you went to a movie theater in LA or Des Moines — the same ten movies played at both.

This narrow list of choices we all had as consumers wasn’t necessarily part of a conspiracy concocted by a few mustache-twirling capitalists; it was largely the practical result of how expensive it’s been for most of human history to produce, market, and distribute products.

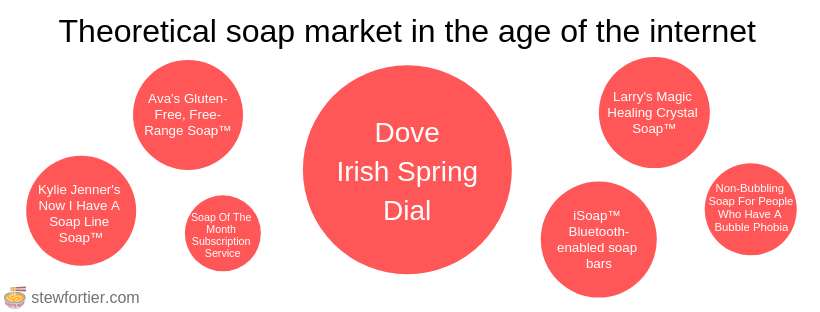

Safeway was not going to drop millions of dollars on a new grocery store only to stock its limited shelf space with Larry’s Magic Healing Crystals™. Each store needed to be filled with affordable, mass-manufactured items that appealed to a broad audience. There was no space for the obscure, niche stuff that didn’t sell well.

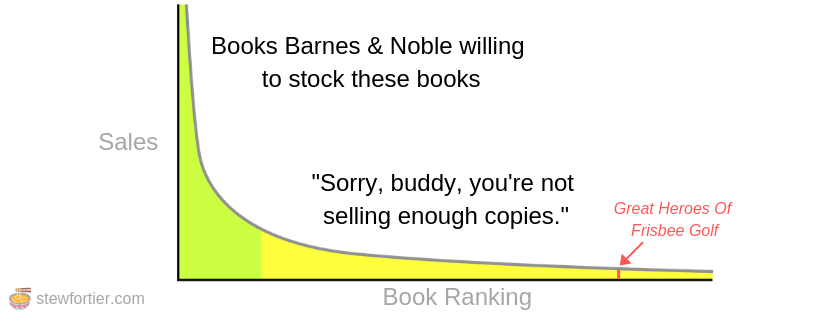

The same was true of a retailer like Barnes & Noble who was not going to drop a few million bucks on a new bookstore only to line the shelves with Great Heroes of Frisbee Golf, Volumes Seven through Twelve (1936-1975). There are more Stephen King fans than frisbee golf connoisseurs and B&N ain’t running a non-profit.

“Sorry, buddy, but nobody cares about your [book/song/specialty coffee beans/clothing line]”

All of this was bad news for people who had a message or a product that might not hold mass appeal. There may have been plenty of frisbee golf fans around the world who would love the entire Great Heroes of Frisbee Golf series, but very few in each submarket. And without a major distribution deal, most frisbee fans were unlikely to even hear of your book, making it even harder to prove demand and convince a big retailer to carry you in the first place.

Chicken, meet egg.

The internet is taking a sledgehammer to the chicken-or-the-egg problem, though, and is leaving nothing but scattered bits of shell — and opportunity — in its wake.

You can’t spell “opportunity” without “awareness”

Fun fact: you can’t capitalize on an opportunity that you’re not aware of. You also can’t buy a book you’ve never heard of. And you definitely can’t order a set of Larry’s Magic Healing Crystals™ without first knowing they exist.

It follows, then, that the ability for information to move between humans is the lifeblood of opportunity. And for most of human history, it’s been a huge pain in the ass to move around information. It’s easy to forget that this is was what cutting-edge global communication technology used to look like:

The internet, 350 years ago

Today, half of the Earth is hooked up to each other via cheap, accessible computers that serve as opportunity machines, removing an enormous amount of friction in our ability to transmit information and hear about things that might deeply interest us, improve our lives, etc.

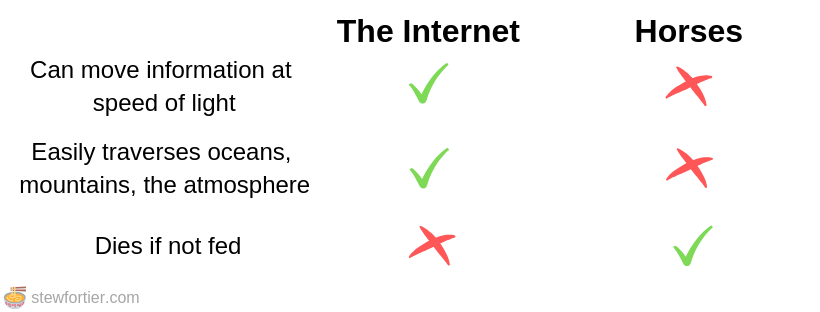

Let’s reflect on just how far we’ve come:

So what are the tangible impacts of our newfound ability to move around information quickly and cheaply? More specifically, how does it affect the nature of economic opportunity?

There are at least two big things that the internet has done, and both have direct implications for how we can make money and build a career. They’re probably conventional wisdom at this point, but let’s do a quick refresher on what they are.

1. The internet has brought the cost of distribution for digital goods down to essentially nothing.

It’s pretty wild to remember that Barnes & Noble, a company that fundamentally sells ideas, has historically been stuck playing the same game as Safeway, a company that sells tomatoes and beef.

Before the widespread adoption of cheap personal computers, ideas had to be captured in a physical form (a book, novel, encyclopedia, etc.) and were thereby subject to the same laws of physics and markets as the stuff you find in the grocery store.

For those reasons, Great Heroes of Frisbee Golf, Volume Seven (1936-1945) would have had a hard time finding an audience at all.

But the internet has brought the cost of distribution down to essentially zero for products that can be represented in a digital form. Now, an entire frisbee golf book series can just live on Amazon’s digital shelves as an ebook incurring a negligible cost for the publisher and Amazon. Having a book in the “Long Tail” of sales rankings doesn’t mean the certain death it may have in the recent past.

2. The internet has made it remarkably easy to find and reach the people who will love your product, song, book, class, whatever.

The geographical boundaries that have long defined tribes are melting away, leaving only ideological ones.

Instead of taking out an ad in a local paper in the hope of finding a few people who might buy whatever you’re selling, you can get on Twitter, search for people everywhere on Earth talking about ultra-specific topics, and send them a direct message that will almost certainly land in front of them — for free or next to nothing.

The friction to locate, qualify, and get a message in front of the right people is shockingly low, historically-speaking.

1 + 1 = ?

Taken together, these two forces are driving some enormous changes in the economy.

“The Market” is breaking into niche markets where there were none before

In a nutshell, the internet enables sizable niche markets to exist where they simply couldn’t before.

For example, imagine you were a budding (bubbling?) soap entrepreneur twenty years ago. That would have been pretty brutal.

If you wanted your soap line to make any real money, you had to go head-to-head against the big boys and try to convince a major distributor to carry you alongside them.

Today, you could circumvent the system altogether by hosting a Shopify store and distributing, marketing, and selling the soap yourself.

The challenge for the entrepreneur shifts from the nearly-impossible task of getting into a major chain store to the difficult, but the less existentially-risky task of finding and broadcasting a message directly to the people who will love your product.

In theory, the internet enables a thriving long tail of soap products to exist.*

Today, soap entrepreneurs shouldn't necessarily default to asking “how do I convince a major retailer, publisher, studio to buy into what I’m doing?” Instead, they could opt for “how do I find the end customers who will love what I’m selling so that I can remove the middleman altogether?”

It's possible you'll still need a major distribution deal to succeed massively -- but for the first time in history, that's not the only way.

* In practice, I have done absolutely no research on the soap industry.

Many of these “niches” are huge

It’s easy to hear the word “niche” and imagine a market that is almost trivially small.

Aw, is that your niche over there? So cute.

But the internet keeps revealing just how many enormous, untapped niche markets exist,

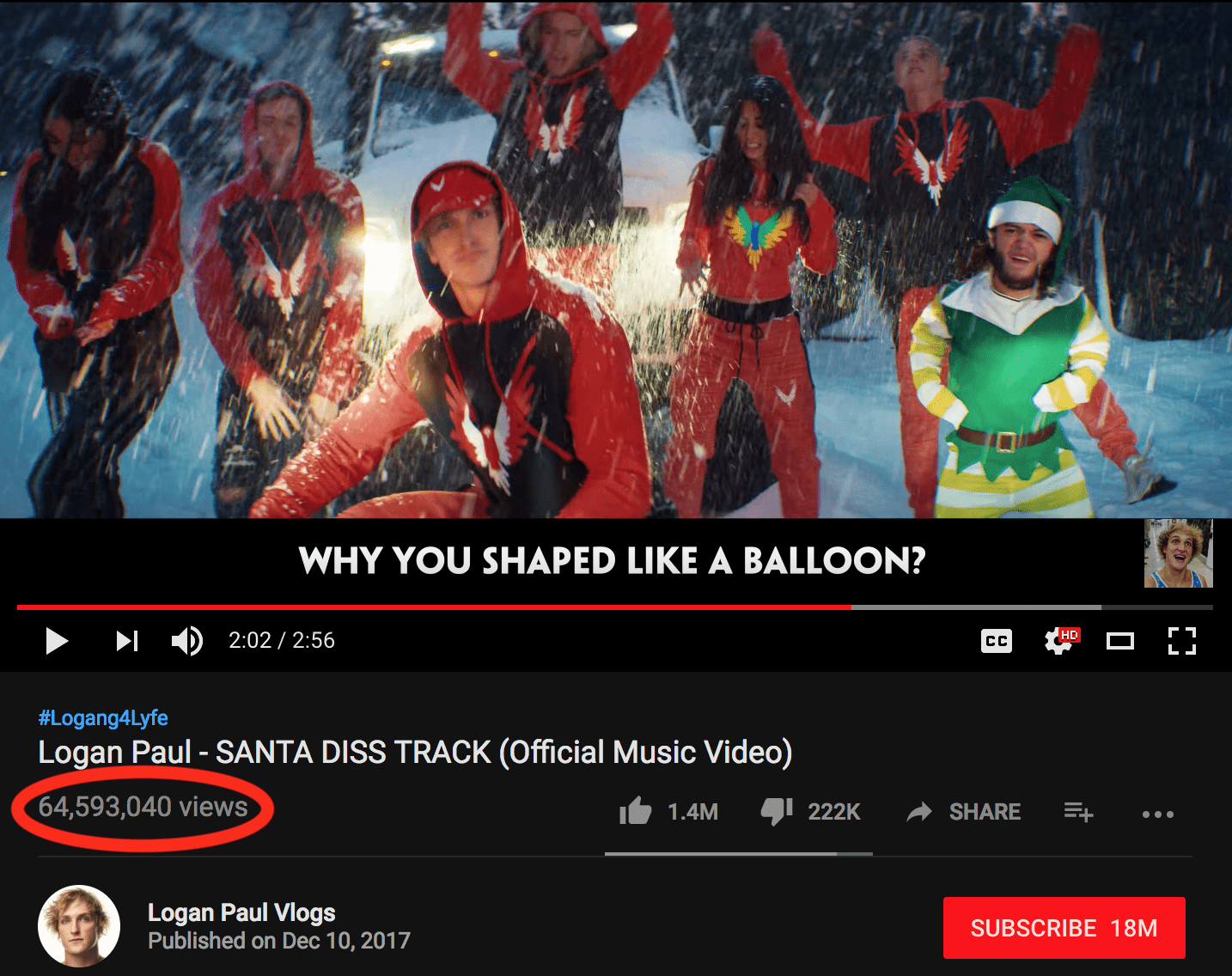

One place where this is blindingly obvious is in the media industry, as demonstrated by people like Logan Paul.

For better or worse, he’s proven that millions of people are apparently interested in watching a person with a double-digit IQ insult Santa Clause in a self-produced rap music video entitled “SANTA DISS TRACK.”

That video alone has garnered over 64,500,000 million views, vastly more than most major media companies could ever hope to attain with their best content.

For context, here’s how The Oscars did last year:

This phenomenon is showing up all over the place.

Take Delighted, a company that pulls in millions of dollars every year by making it easy to embed a “how likely are you to recommend this to a friend” survey into your website. That’s a hilariously specific business. Or MVMT, who brought in $70 Million last year selling niche watches on Instagram.

Hell, take Scrivener, the software I’m using to write this. A school teacher in London built the first version in his spare time ten years ago and started selling it for $50 a pop to writers. It’s now a real company with a real team and real revenue.

To get even more niche, there’s also apparently some dude who made half a million bucks teaching people how to use Scrivener. Niche-ception! It’s madness, and neither of these businesses could exist without the internet.

It used to make sense to kill a business idea when it wasn't obvious that there was a big market for it. But, today, maybe we should think twice and consider how much easier it is to find the people who will love what we’re doing.

Today, we have more freedom to not water down our work

When the distribution channels in an industry are expensive and tightly-controlled, there’s often pressure to water down what goes through it in an attempt to make it more “appealing” to a mass audience.

Every major, traditional studio with a firm grasp on distribution told Jenny Han they’d only cast a white, not an Asian-American, actor as the lead in her movie To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before. Thankfully, she turned them all down until the internet-first, up-and-coming Netflix content team gave her full creative control.

Their insistence on whitewashing the film is, in part, a function of pre-internet distribution, where the "mass market" must be catered to (in this case, white Americans in the U.S.).

It’s our job as professional niche-hunters go directly to the 100,000 people who will love what we’re doing and forget about the million who might kind of like it if we watered things down.

The Age Of The Niche has only just begun

“People don’t have any idea yet how impactful the internet is going to be and that this is still day one in such a big way.” - Jeff Bezos

We’re still in the early days of the internet, which could mean we’re only just beginning to see what the niche economy looks like.

And if the future looks anything like the present, then opportunities abound for those willing to combine their skills in a unique way to conquer some exciting niche.

Happy niche hunting!

An honorable mention is due to Taylor Pearson's great, short book “The End Of Jobs” which elaborates on and inspired many of the ideas here.